We had given short shrift to eastern Montana during our three year Journey and we’re making up for it now. But since we were still unable to schedule completion of the Dinosaur Trail, that simply means that we’ll have to come back again. At least we’ve now been to both ends.

Crow Agency, MT is the actual location of the Little Big Horn Battlefield, but we parked our rig about 12 miles away in Hardin. It is a very small town (pop. 3,600), but it has a super qualified truck facility that found out why we were running on only three of the dually wheels on our truck instead of all four!

On The Journey in 2011, we’d bypassed the Little Big Horn site because the bulk of its antiquities, we learned, had been moved to a federal climate-controlled Arizona warehouse because conditions at the site were inadequate to protect them. We didn’t realize, however, that the heart of the site couldn’t be moved. Thus, the visit this year. We spent two days there.

On Day 1, we took a tour of the visitor’s center – a quick experience since it was minimized and what you really want to see is out in the field. We listened to an impassioned half-hour lecture from a ranger who was so into it that he could have kept us entertained for hours. Then we took a one hour tour with Apsaalooke Tours through the center of the action with a Crow Indian guide (the Crow Federation has an exclusive license to run these tours). I will leave the recast of history to the scores of treatises on the subject, but I will share some pictures and a few sights of wonder.

The road is on a rise that allows one to see down into the field where over 5,000 Native American families were camped – the target of Custer’s mission. You pass named skirmishes along the way that resulted from Custer’s segmentation of his force: Lame White Man Charge, Greasy Grass Ridge, Medicine Tail Coulee, Sharpshooter Ridge, among others.

- The Native American encampment

- Artist’s View

- Wooden Leg Hill

- Keogh-Crazy Horse Fight

- Lame White Man Charge

- Medicine Tail Coulee

The path runs five miles south to the Reno-Benteen Battlefield where the fateful day actually began.

- Reno-Benteen Field

- Reno-Benteen Battle Site Layout

- Reno-Benteen Memorial

Then it returns to Last Stand Hill. We left the tour bus there and continued on foot.

- Now Quiet Field

- Description of Gravestones

- Marble Cavalry Gravestones

- General Custer’s Stone

- Last Stand Hill Memorial

- Last Stand Hill

In 1879, a wooden memorial was the first to be placed on the field. Two years later, Lieutenant Charles F. Roe and the 2nd Cavalry built the granite memorial that marks the top of Last Stand Hill (above). Marble markers locate the spots of the fallen soldiers, while granite markers denote Cheyenne fallen.

The Native American Memorial, completed in 2003, honors the Lakota, Arapaho and Cheyenne losses.

- Entrance to the Memorial

- Arikara Synopsis

- Sioux Synopsis

- Cheyenne-Arapaho Synopsis

- Crazy Horse

- Council Fires

- Cheyenne Role

- Strategy

- Native american Granite Gravestones

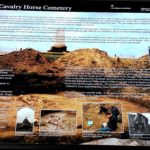

A horse cemetery is also marked.

- Cavalry Horse Marker

- Details of the Cavalry Horse Grave

Walking back down the Hill, we passed the Custer National Cemetery, adjacent to the Visitors Center. It is not the burial place for the victims here; many of those were returned to their homes back east. Custer’s remains were buried a West Point. Now closed to new graves, the cemetery contains the names of many frontier soldiers as well as members of all forces through most of the subsequent wars. There are approximately 4,500 graves in all.

One notable name is Pfc. (posthumously Spec.) Lori Piestewa (White Bear Girl), the first Native American to be killed in a foreign war. Lori, a Hopi, is buried in Tuba City Arizona, but there is a memorial to her here, shown at right. She was one of the brave soldiers involved in the Iraqi attack in 2003 during which she, Jessica Lynch and Shoshana Johnson were taken captive. Lori’s head wound caused her demise shortly thereafter.

When we went back for a second look on Day 2, we also went to the adjacent Custer Battlefield Museum, a private facility located in the town of Garyowen, MT, the only town within the battle site, near the location of the mass Native American camp. It houses a wide collection of artifacts from the battle and from the history of the opposing sides. Out front is a Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, reputed to be the only such site outside of Arlington Cemetery. It was dedicated on the 50th anniversary of the battle and contains the remains of a soldier under Reno’s command.

- Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

- Sitting Bull

- General Custer

The Museum proudly houses a collection of the photography of David F. Barry (1854-1934), whose portraits of Sitting Bull, Gall and many others on both sides are world famous. But tourist cameras are strictly prohibited.

This ended our sojourn through the history of the Little Big Horn. But there was more to see “in the neighborhood.” The first trip was less than desirable because I opted for shortest rather than fastest route and wound up on dirt road for more than half of the 50 miles. The reward at the end was worth it.

One of the very few exact locations known to be reached by the Lewis & Clark Corps of Discovery is Pompey’s Pillar. Rising 150 feet above the Yellowstone with a full acre footprint, this sandstone butte sits 25 miles east of modern Billings. A stele at the summit identifies it as being just under 3,000 feet elevation from sea level. It is a well-documented landmark, named by Capt. Clark after Sacacawea’s son when he and his part of the expedition traveled back toward North Dakota in 1806 to link up with Capt. Lewis. In fact, he carved his name and the date on its wall about half way up on the north side. A snaking stairway leads you to the signature, where chatty volunteers love to swap stories with those of us who’ve explored the whole Trail. That signature was somewhat protected in 1882 when the Northern Pacific Railroad installed a grate over it, , but it was not until 1954 that the current shield was put in place. Meanwhile, the curious have had a field day of scratching their own graffiti at the site.

- The Pillar

- The Route Up

- The Famous Signture

Declared a National Historic site in 1965, it was in private hands until 1991, when it was acquired by the BLM. They manage not only the landmark but an informative museum in the Visitors Center that opened in 2006.

- Bull Boat, made from a single Bison hide

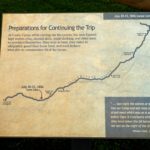

- Overall Route Map

- Preparation

A ranger who accompanied us between the signature location and the summit pointed out an image in the rock wall. Native Americans called the Pillar “the place where the mountain lion lies,” and the image we saw might have been the reason. I didn’t find it immediately, but when he highlighte it with a laser pointer, it became clear.

I made the return trip the long way on roads that were all paved. And I’m doubly glad I did, because I got to visit Rosebud Creek, scene of at least two significant moments. In chronological order, Wm. Clark and party passed through here after visiting the Pillar. His documentation of the region was a major impetus to the subsequent fur trade that overran the area. In fact, buffalo hunters took over 40,000 buffalo pelts in the 1870’s and ‘80’s, seriously affecting the Native American food chain and causing uprisings. That, in large part, led to the second Rosebud moment. On July 18, 1876, General George Crook fought a fierce battle with Crazy Horse and his Sioux/Cheyenne friends. Despite being supported by a force of Crow and Shoshone, history will say that Crook left the field defeated and withdrew to his camp in Sheridan, Wyoming. He decided to sit out the Little Bighorn campaign eight days later, and historians have a lot to say about that decision.

- The Marker

- One View

- Another View

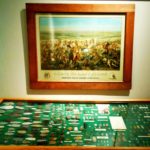

But we still weren’t done. The Big Horn County Historical Museum opened in 1979 east of Hardin. Originally 22 acres, expanded to 35 and added a new museum building in 2012. Over the years, 24 authentic historic structures from throughout the county have supplemented the site’s original farmhouse and barn, each containing exhibits of the era. The new museum building includes a gift shop, research library, archives and offices.

Sadly, we only had a brief time left — only enough to skim the main museum building before heading back to camp to pack up for departure the following morning.