On our three year Journey, we didn’t include a stop in Montana’s Capitol. We went through it as we traveled from Great Falls to Bozeman, but our prime focus at that time was on our beloved Teddy Bear Onyx, who breathed his last in Bozeman at age 15. So we made up for it by spending a week there this time.

Helena is a lovely, fascinating city. Our first adventure involved the Last Chance Gulch Train. We departed from the city’s historical museum in a 100-plus foot Choo-Choo on wheels. Recognizing that our train was half again longer than a semi-truck, we were amazed as our driver deftly wound us through the streets of the city for an hour, giving us sense, pointing out landmarks and regaling us with tales. Most of all, she increased our thirst for more.

The “last chance” appellation refers to the miners who worked the city’s gold claims and provided so much heritage that Main Street is Last Chance Gulch! As a bonus, our train trip entitled us to freebies along the way as we explored the shoppes along the Gulch. A stroll down Last Chance Gulch gave us a chance to eye the many emporia, along with the street art, that we had rolled past on the trolley. The last of the three pictures below, taken further down the street, shows the Gulch in an earlier time!

-

-

One of many sculptures along Last Chance Gulch

-

-

Mural along Last Chance Gulch

-

-

Old miner’s cabin on exhibit.

Now it was time to search out the treasures to which we’d been introduced. We started with Montana’s Museum, from whose doorsteps our loco-tour had departed. Outside the front door is a larger than life metal sculpture, Herd Bull, by Benji Daniels. Nearly 25 feet across from horn tip to horn tip, it was built from scrap sheet metal and represents both the vast importance (size) and tragic destruction (skeleton) of this classic American symbol. When we first arrived for the trolley ride, a class field trip was using it as a jungle gym!

Now it was time to search out the treasures to which we’d been introduced. We started with Montana’s Museum, from whose doorsteps our loco-tour had departed. Outside the front door is a larger than life metal sculpture, Herd Bull, by Benji Daniels. Nearly 25 feet across from horn tip to horn tip, it was built from scrap sheet metal and represents both the vast importance (size) and tragic destruction (skeleton) of this classic American symbol. When we first arrived for the trolley ride, a class field trip was using it as a jungle gym!

There were five galleries within the Museum. One celebrated Charlie Russell, a nice refresher for us since it had been two years since we visited Russell’s home and gallery in Great Falls. Eighty works ran the gamut from flat and 3D art to his illustrated letters.

-

-

Charlie Russell

-

-

On The Hunt

-

-

The Stagecoach

-

-

Russell Statuary

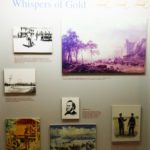

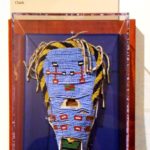

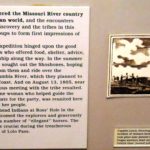

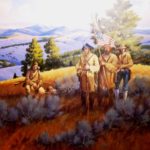

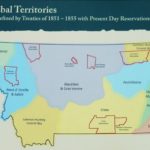

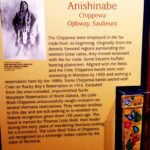

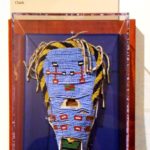

The permanent collections also included a series of exhibits that chronicled life in the territory, dating back 12,000 years and bringing us into the 20th century. Neither Empty nor Unknown is an exhibit chronicling the life of the six Native American tribal groups that Lewis and Clark met – or often failed to meet because of the region’s vastness and because he was traveling the rivers while they were off hunting! The first three pictures are a sampling of more than a dozen describing the Native American nations.

-

-

Sioux

-

-

Cheyenne

-

-

Chippewa

-

-

Native American Beadwork

-

-

Can you find the baby owl?

-

-

Dog and Horse with Travois

-

-

Salish Fishing Basket

-

-

Bison Hide Robe

-

-

Sacred Animals

There was heavy emphasis on L&C; the Corps was there, nearing the headwaters of the Missouri, in the summer of 1805.

-

-

A Successful Encounter

-

-

On the Trail

-

-

On the River

The journey continues as Montana emerges, experiencing hard times and boom years.

-

-

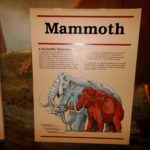

Fragments from the Pleistocene Era

-

-

Remnants of the Mining Industry

-

-

One of many exhibit settings

-

-

The Protecters

-

-

Commerce on the River

-

-

The Railroad Cometh!

Big Medicine

On the upper floor stood Big Medicine, a white bison born on the Flathead Indian Reservation on May 3, 1933. Named in recognition of attributed spiritual powers, he epitomized the importance that such births meant to the Native Americans. Not a true albino, he had blue eyes and a brown hump. When he died in 1959, he had exceeded the average life span by one third, at which point his coat was well worn and retained that way in preser-vation. At one time, he was the second most popular attraction in the state –after Yellowstone National Park!

St. Helena’s Cathedral dominates the landscape. It has a congregation of about 1,700. Financed in large part by Thomas Cruse, a local gold miner/philanthropist, the Cathedral’s cornerstone was laid in 1908. Built of Indiana limestone instead of Montana sandstone, it actually took until 1924 to complete. But the dedication was on Christmas Day 1914– five days after Cruse’s death at 78. His was the first funeral to be held there. Over the succeeding years, most recently in 2002, it has repeatedly undergone restoration and renovation. Repairs necessitated by a series of earthquakes in 1935 took three years to complete. At this point, pictures will be better than words.

The Capitol sits on an expanse directly across from the Natural Historical Society. Construction, of sandstone and granite, began in 1899, and the major financial resource was . . . Thomas Cruse! It was designed by Frank Mills Andrews, and it was completed in 1902. Like so many others, received wings on both sides in 1909 and 1912.

You enter under the dome, and the rotunda is impressively decorated by artwork representing the four forces creating the state: Native Americans, gold miners, cowboys, and explorers. Straight ahead is the Grand Stairway. The first landing honors two people with statues: Wilbur Fisk Sanders, lawyer, Civil War veteran, forceful prosecutor and one of Montana’s first U.S. Senators; and Jeannette Rankin, leading voice for women’s suffrage, and first democratically elected woman (U.S. Representative, 1916-1918) and lifetime advocate of women and peace. Her first vote in Congress was against entry into W.W. I. She did not survive re-election then, but she was returned to the House in 1940 and cast the only dissenting vote against our entry into W.W. II. Hallways to either side lead to the Governor’s and the Secretary of State’s offices.

Continuing up the staircase, one reaches a mezzanine that heralds Montana’s favorite son, Mike Mansfield, longest serving Senate majority leader in history, and his wife Maureen. The legislative and judicial functions are found at this level. The room to the east has had three lives: Senate Chamber, Supreme Court Chamber and Meeting Room. The opposite room was originally the House Chamber and now houses the Senate. The much larger rooms in the added wings hold the House to the west and the Law Library to the east. The Court now has its own Judiciary building elsewhere in town. A statue of Thomas Francis Meagher, a former governor of the Montana Territory and commander of the Irish Brigade in the Civil War, was added to the front lawn on July 4, 1905,

-

-

The Capitol

-

-

Thomas Francis Meagher

-

-

View of Gov. Meagher

-

-

Wilbur Fisk Sanders

-

-

Jeanette Rankin

-

-

Sen. Mike and Maureen Mansfield

Throughout the building are depictions of all the elements that have created Montana’s unique character. As in the Historic Society, considerable attention is paid to the Corps of Discovery. It’s culminated, in fact, in the piece de resistance: a painting by Charles Russell in the House Chamber, so large that Charlie had to raise the roof of his studio to complete it. It’s entitled Lewis and Clark Meeting the Flathead Indians at Ross’ Hole

-

-

The Dome

-

-

The Railroad

-

-

House Chamber with Russell’s epic work

Montana’s Original Governor’s Mansion was built in 1888 as a private residence. The state bought it in 1913, and it housed nine chief executives and their families until a new (ugly modern) mansion was built in 1959. It had a variety of uses for the next 20 years until 1980, when it became an established city tourist asset and was restored to its 1913 image.

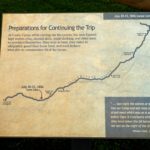

After a two week rigorous ordeal to portage the nine Great Falls in the steaming July heat, the Corps continued upstream through a cavernous section of the River half way between the Falls and today’s Helena. Limestone cliffs towered almost a quarter mile above them and extended right down into the deep water. Meriwether Lewis’s fascination with this geography was one driving force back to the Helena area for us. In his journal, Lewis wrote, “I shall call this place: Gates of the Mountains.” We were not about to miss the experience of taking a tour boat ride through it.

The boats leave from Upper Holter Lake and provide a ninety minute, slow moving, vividly described journey down through Gates of The Mountains and back. Our captain deftly approached the passage from four or five different directions so we could envision how it might have looked to the expedition 208 years ago. He tirelessly explained geographic features, flora and fauna along the route. He offered to put folks ashore at the Meriwether Picnic Area, one of the very few spots in the stretch that a boat could land (and where L&C likely camped). It was near this area, in Mann Gulch in 1949, where a raging forest fire caused the worst disaster in smoke-jumper history — thirteen men were lost. Again, our captain narrated a description of the disaster that was a virtual mise-en-scène. We were also driven in close enough to see petroglyphs left by inhabitants prior to L&C.

-

-

Entrance

-

-

Steep Cliffs

-

-

Trees are plentiful.

-

-

Many caves.

-

-

Seemingly goes on forever.

-

-

One of the few places to land.

-

-

Local fauna

-

-

Site of the Mann Gulch Fire

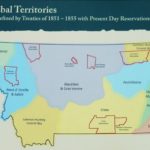

We made a last trip downtown to visit the Great Northern Town Center. We knew it was a boutique-y outdoor shopping center, but it also promised a L&C commemorative trail, and anything attached to The Expedition intrigues us. We got there before the shoppes opened and the carousel started to turn, so we walked the esplanades with few others. It was filled with plaques that told snippets of the L&C story along a “river” in the pavement. It’s also interspersed with sculpture.

-

-

Entrance Arch

-

-

Story-Teller

-

-

Tribal Territories

-

-

Local Native

-

-

Other Friends

-

-

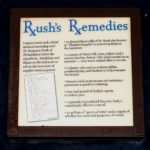

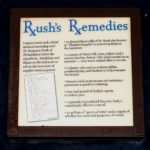

READ ABOUT DR. RUSH’S PILLS!

-

-

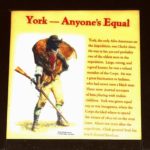

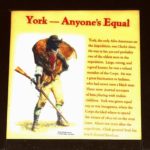

Clark’s Slave York

-

-

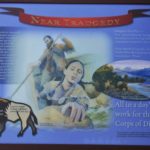

Near Tragedy averted by Sacacawea

-

-

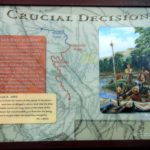

What to do when the Missouri forked.

-

-

At war with the Blackfeet

-

-

The Corps splits up on the return trip.

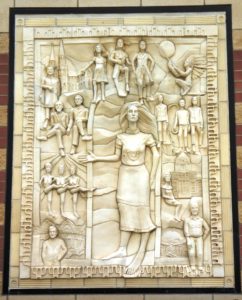

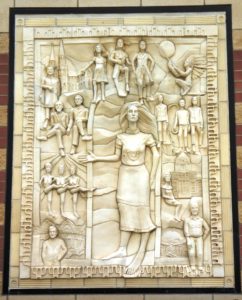

The Town Center exhibit that really peaked our interest was a clay frieze entitled Entrepreneurial Spirit of Helena, created by Seattle artist Kristine Veith in 2003 caused a stir when first unveiled. It took me a trip through Google to identify all of the images portrayed, and what a collection! They include Alan Nicholson, developer of the Town Center; Lewis; Clark; Sacacawea; Thomas Cruse; Jeannette Rankin and Wilbur Sanders. Bishop John Carroll builder of the Cathedral and founder of Carroll College in the first 20th century decade is there, along with Thomas C. Power, merchant and first Senator; three representative Chinese laborers; and Archie Bray, brick maker and philanthropist whose Foundation for Ceramic Arts thrives today. A large figure of “Helena” is in the center, representing the city’s name, applied by the many Minnesota miners from St. Helena. But there’s more. There are three brothel dancers in the montage. Josephine “Chicago Jo” Hensley, an Irish immigrant lass who worked her way west from NYC on her back, moved to Helena and opened a “house” in 1867. Her business grew exponentially; she owned four major establishments and partnerships in many other businesses in the city. Her death, in 1890, prompted a huge funeral and many tributes.

The Town Center exhibit that really peaked our interest was a clay frieze entitled Entrepreneurial Spirit of Helena, created by Seattle artist Kristine Veith in 2003 caused a stir when first unveiled. It took me a trip through Google to identify all of the images portrayed, and what a collection! They include Alan Nicholson, developer of the Town Center; Lewis; Clark; Sacacawea; Thomas Cruse; Jeannette Rankin and Wilbur Sanders. Bishop John Carroll builder of the Cathedral and founder of Carroll College in the first 20th century decade is there, along with Thomas C. Power, merchant and first Senator; three representative Chinese laborers; and Archie Bray, brick maker and philanthropist whose Foundation for Ceramic Arts thrives today. A large figure of “Helena” is in the center, representing the city’s name, applied by the many Minnesota miners from St. Helena. But there’s more. There are three brothel dancers in the montage. Josephine “Chicago Jo” Hensley, an Irish immigrant lass who worked her way west from NYC on her back, moved to Helena and opened a “house” in 1867. Her business grew exponentially; she owned four major establishments and partnerships in many other businesses in the city. Her death, in 1890, prompted a huge funeral and many tributes.

And still more. When the work was first unveiled, it was rumored that one of the dancers was a spittin’ image of Montana Governor Judy Martz, then in office as the State’s female top executive. Veith denied even knowing what the governor looked like!

So that’s Helena. So much more than we expected. I’m still not sure we gave it full justice!