In 2011, we’d breezed through the eastern side of Wyoming on the way to Montana, visiting Cheyenne, Casper and Buffalo. Now we were breezing through its southeast corner! Someday, we promise to come back and spend a more leisurely sojourn, including Cody and Wyoming’s part of Yellowstone. We bypassed Cheyenne and stopped in Laramie for a night. Then we moved on to Fort Laramie, 115 miles close to the South Dakota border, for the following night.

Laramie gave us nothing to write about. I have neither notes nor photographs nor literature to spark my recollection. Oh yes, I have one memory. The campground was an overpriced KOA and the Wi-Fi was broken! So I’ll skip it instead of faking it with Google and move on to Fort Laramie, where our visit is worth writing about.

The ad for the Chuck Wagon Campground said, “If you love trains, this is the place for you.” It was a tiny place, run by Grandma and Grandpa Hofrock from their house on the property. It was 50 yards from a main line with trains passing every 20 minutes — thanks in part to an oil depot opened in 2014 — blowing their horns for the adjacent street crossing. The Hofrocks worked for national railroads all their lives, mostly in Atlanta, and were oblivious to the noise. There was a small, tasty restaurant on the property owned by a transplanted New York couple — he served and she cooked.

We were there before noon and used the day to travel two miles to Fort Laramie itself. Located on the confluence of the Laramie and North Platte Rivers, it started life in 1834 as Fort William, and in 1841 was rebuilt as Fort John, where it served as a critical way-station for Mormons and westward emigrants to California and Oregon. Purchased by the Government in 1849, it became the largest and most important military post of the Northern Plains. It hosted the Pony Express, stagecoaches and the transcontinental telegraph. It also hosted the signing of two Native American treaties. But it also dispatched military excursions to overrun and confine the original settlers. Auctioned to homesteaders in 1890, it gradually fell into ruin until 1938, when it became part of the National Park System. Since then, twelve of its 50+ buildings have been restored and refurnished to its glory days. Approximately two dozen buildings surround the parade ground, with the others scattered beyond.

- Early Days

- Whispers of Gold

- The 1860’s

- The 1880’s — Golden Years

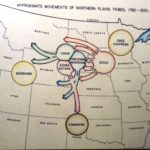

- Native American Migration

- The Bakeries

- Barracks

- BOQ — “Old Bedlam!”

- Old Bedlam restored

- Officer Housing

- More Officer Housing

- The Sutler’s Store

A large ruins is all that’s left of the Rustic Hotel, built in 1876 by the Post Trader John Collins to accommodate the huge influx of gold seekers.

- The Rustic Hotel Story

- Rustic Hotel Remains

Another site is far more touching. Sinte Gleska — Spotted Tail — leader of the Brule Sioux, trusted Colonel Henry Maynadier, commander of the Fort in 1866. Maynadier was one of a small group of officers who, while doing his duty, opposed the treatment doled out to the Indians. On March 8th of that year, the colonel rode out to meet his Spotted Tail and escort him back to the Fort. Spotted Tail was carrying the remains and possessions of his deceased daughter, whose deathbed plea was to be buried near her grandfather on the Fort’s grounds and to urge her father to continue seeking peace with the white intruders. His daughter, Mni Akuwin — Brings Water Home Woman – was laid to rest on a scaffold in full ceremony. Maynadier wrote to his wife, “…after what I witnessed in the Council room and the graveyard, I can never be willing to see these people swindled, ill-treated and abused as they have been.” Regrettably, Spotted Tail was assassinated by his own people five years later for his part in seeking peace.

- Burial of Mni Akuwin (Brings Water Home Woman)

- The Story of Sinte Gleska and Col. Maynadier

- The Story continued

On the way back from the Fort, we encountered the story of the Fort Laramie Bridge. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 created the Great Sioux Reservation. The Iron Bridge was opened in 1876 because there was a need to transport materials and supplies to the governing agencies. Unfortunately, it quickly became the route of choice for gold diggers illegally entering and mining the Reservation, leading to the great Sioux wars. Abandoned in 1958, it is preserved locally as a footbridge.

- Story of the Ft. Laramie Bridge

- The preserved Ft. Laramie Bridge

The next morning, I had to backtrack about 20 miles to get diesel fuel, and it gave me an opportunity to learn more about the North Platte and its significance in western expansion via roadside placards.

- The North Platte River

- The North Platte River

- The North Platte River

As we pulled out of Fort Laramie and Wyoming, we were “anticipatorily agog” about the show ahead of us.