During our three year Journey, we made a number of stops in Idaho. But another on our list was still unexplored. We headed due south from Missoula to the city of Arco so we could visit the Craters of the Moon National Monument.

We lucked out at our campground of choice, Mountain View. Not only was the rate reasonable; we were entitled to eggs, pancakes and coffee every morning. We did every other day, and padded them with sausage or bacon for a nominal extra charge. And the free meal benefit ended for the season on the day after we left! The view from the campground was unusually great, too, and it included a mountain that every Arco high school class has emblazoned it with its graduation year!

Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve is the largest volcanic plain in the U.S. It was formed by a series of eruptions along a 62 mile fault in the Snake River Valley called The Great Rift. Eruptions began as long as 15,000 years ago and continued until about 2,000 years ago. Future eruptions are expected, but not for at least 100 and maybe as much as 900 years from now. So don’t cancel plans to visit.

Actually, eruptions began millions of years earlier. Prevailing theory states that a hot spot under the area pushed magma, first a thicker rhyolite (the volcanic equivalent of granite) and later the top covering of basalt, creating a new landscape as much as 4,000 feet thick. The hot spot hasn’t moved, but the earth’s plates have, and the hot spot is now believed to be under Yellowstone National Park.

The total Preserve is 1,100 square miles, about the size of Rhode Island. There are actual three fields, Craters of the Moon itself being the largest. Two others, believed to have occurred at a time when the Shoshone were present to see them, are the Wapi and Kings Bowl fields. Tribal lore alludes to a giant angry snake squeezing the mountain and causing it to belch fiery liquid. As with virtually every geological formation, there’s a new lexicon to learn: cinder cones, spatter cones, vents, fissures, lava tubes, lava bombs, tree molds, rafted blocks . . . and others.

We toured the fields as best we could. My aching back — a permanent arthritic affliction — had begun to restrict the distance I could walk. And Dot was no better off; she had a foot issue that was destined for surgery when we got south for the winter. So after a review of the Visitors Center maps and orientation, we drove the circuit and roamed off it as best we could. All was not lost; we got a broad impression of the formations, and we saw the interaction of the cold magma and the growing things that survive in its environment. We learned considerably more than is detailed here, but we hope the photos below will stimulate your interest, either in person or virtually. They’re really not suitable for captioning, but you’ll get a random look at the picture

Unbeknownst to us, there was a second attraction to be seen in the area. Arco has the distinction of being the first city ever to be electrified by atomic energy.

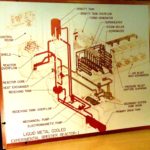

Not long after W.W. II, the Department of Energy began to explore the concept of a breeder reactor to generate electricity, espoused by Enrico Fermi and his colleague, Howard Zinn. The Argonne National Laboratory at U-Chicago, originally involved in the Manhattan Project, established a facility in Idaho called EBR-I (Experimental Breeder Reactor).

The small team led by Zinn and project engineer Harold Lichtenberger, received their just reward when, on December 20, 1951, the switch was thrown and a string of four 200 watt bulbs glowed brightly. The capacity was raised the very next day, and EBR-I generated electricity for 13 years until it was replaced by EBR-II, which in turn ran through 1994. In 1966, EBR-I was dubbed a National Historic Landmark and became the museum it is today. There’s a self-guided tour through the entire facility and process, and hosts field questions and make sure you get the answer. Poised in the middle of the desert, the entire area is the 890 square mile Idaho National Laboratory. In addition to the reactors, INL’s 4,000 employees pursue countless engineering projects.

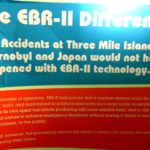

One of the major functions of the installation is the processing of nuclear “leftovers” from installations throughout the country. It’s not simply “waste” — the site was the recipient of all the core debris — 148 tons of it — from the Three Mile Island meltdown. The story of the preparation and execution of that transfer, by rail without incident, is documented in the Museum. Also found there are examples of the Lab’s attempt to create nuclear airplane engines, an experiment that was abandoned.

- Three Mile Island Project

- Testing (over-testing) the containers

- 100% safe transit in these

Glowing from our discoveries, we pushed on southward to the next state.